MemWorks built a comprehensive understanding of the challenges faced by workforce participants living in poverty before developing evidence-based solutions to address them. Meeting with workforce participants, and the organizations that support them, to understand their experience pursuing postsecondary education and seeking living-wage career paths was a core focus of MemWorks. We conducted surveys, interviews, and focus groups with more than 100 postsecondary students, workforce participants, employers, and nonprofit staff who provide workforce services.

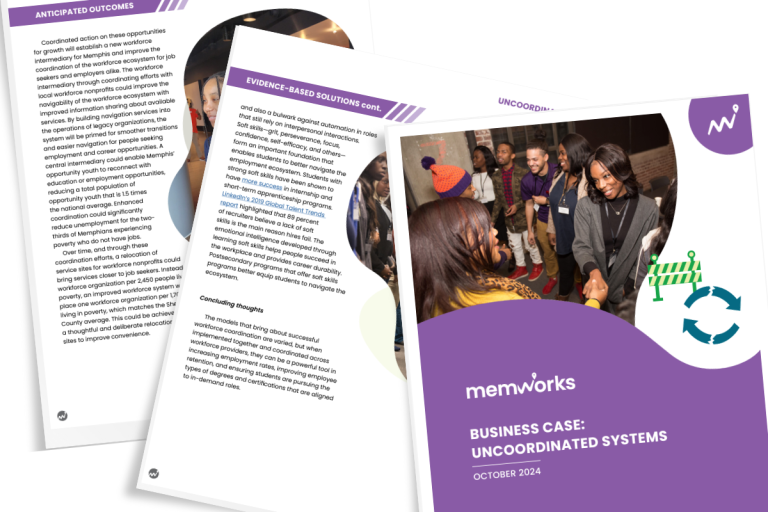

This blog post focuses on social capital and the difference a support network can make for a person pursuing a living-wage career path. Social capital is defined as “the networks of relationships among people who live and work in a particular community, enabling that community to function effectively.” When we think about social capital, we think about the bonds created between career coach and training program participant, mentor and mentee, or between peers learning alongside each other in a postsecondary program.

Advocates and coaches are confidence builders.

“[My coach will] kind of, like…I mean, I wouldn’t say a therapist, but she feels like a therapist, and she does that sometimes. But she asks about everything. She makes sure that we’re doing fine, that we don’t need anything, that we’re making and meeting goals that we’ve set for ourselves. She tries to see where we’re at with the coursework, how we’re feeling about it, and everything like that.”

– Technical Training Alum

Job-seeking Memphians value the role of advocates and coaches who support them. Many training participants and students discussed the importance of an advocate, coach, or mentor in their education and employment journeys. We frequently heard that these mentors made a difference in whether students graduated or dropped out.

Beyond training programs, people often stay in touch with their mentors and coaches and benefit from their connections to employers during their job search. This first advocate can immensely help job-seekers who are experiencing poverty as they often lack readily available access to similarly well-connected mentors and advocates outside of their programs.

Colleagues and peers fill gaps in resources and institutional support.

“I haven’t felt judged by anyone here. I felt like that’s what I expected. I’m just gonna be honest, it’s the first thing I expected. But they had a total opposite reaction. They have been helpful. I’m working where I am because of them.”

– HopeWorks Participant

Training participants and students frequently shared that they rely on the community around them to fill a gap in resources and institutional support. Many focus group participants attributed their success to their community and support from their peers. Training staff shared that some students lack strong social bonds outside the program, emphasizing the importance of creating a sense of community and strong ties between students.

“The most important thing I think, for our cohort, was the way we bonded with each other.”

– The Collective Blueprint Participant

Several students shared examples of how community fills in where there is a lack of resources or institutional support, such as carpooling, emotional support, and building professional networks.

In other cases, the absence of a community bond was stark. At one postsecondary institution, students desired to connect with each other, but felt like there were limited opportunities or events available to do so. Some students tried to set up study groups, but childcare became a barrier to keeping the group going.

While they can appear informal, strong social capital bonds can make or break students entering a training program or graduates entering the workforce. Building these bonds with coaches, mentors, and advocates can build confidence and provide direction. Strengthening relationships among peers can expand a person’s safety net enabling them to be more resilient and aware of available opportunities.